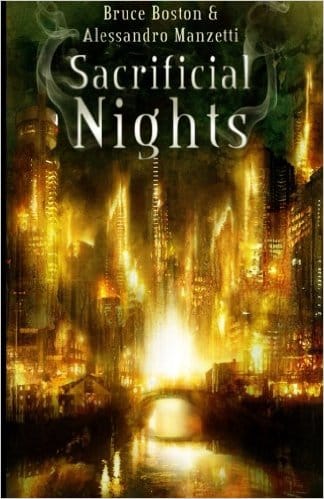

Sacrificial Nights by Bruce Boston & Alessandro Manzetti 2016 Kipple Officina Libraria (Italy). 123 pages. www.kipple.it

Sacrificial Nights contains poems by each of the authors separately and some in collaboration. Most of the poems are long, and they are set in Sacrificial City, a hardcore lawless urban district. The poems build, and some characters reappear from poem to poem. The poems are meant to be read in order, but I would recommend not in one sitting so that the darkness doesn’t overwhelm. There will come a point somewhere after the middle of the book where it will be hard to stop reading. Make sure you have your breath when you get there.

While I expect this book to be nominated for the Stoker and some of the poems to receive consideration for the Rhysling, it is, more than anything, noir, right down to the detective who fears his doom. There are places where fantastical things are implied, but they are generally not nailed down leaving this in the liminal spaces of speculative poetry. I am sure the whole book qualifies as horror. I leave the question of how much of the book qualifies as speculative to those who care to tease out the subtle differences.

I consider this a book of poetry noir, and nothing could be more natural. Noir is an unusual literary movement in that it came from cinema rather than the written word, and this book certainly relates back to that origin. Sacrificial Nights would make a helluva noir film full of strong images and actions. But the funny thing is, one of the hallmarks of noir film and noir fiction is its inherent poetry, the poetry of the mean streets, and a dark poetry of fatalism, betrayal, and a morality far more brutal than anything discussed in clean suburban sermons. Perhaps books such as this are its final destination.

Some of the poetry is straightforward such as this from “Requiem in a Taxi”:

The driver turns to her,

his face like that of her father,

lord of whiskey and punches,

buried now three years

in a loose blue suit.

Some is more figurative such as this excerpt from “Deep in His Coma”:

the head of the future

hissing from a manhole

with the language of a snake,

This book is really one story of dangerous streets with many characters: hookers, serial killers, arsonists, hookers, pimps, strippers, hookers, thieves, and psychopaths. There are some graphically violent moments, but the poetry doesn’t dwell on the horrific scenes. It expresses then and steps away leaving the reader to fill in as much or as little detail as she wishes.

There has been much critical discussion through the years of the difference between horror and terror with the first being a physical threat and the latter psychological. I believe there needs to be a similar division in noir between that which dwells in the physical pain and darkness, and that which dwells in the psychological darkness and fear. In the first the worst happens, and then is exceeded. In the second the anticipation of evil, corruption, and betrayal is worse, and the awful reality is almost a relief. Call the first the ‘blacker outside’ school and the key component is that the reality is worse than you ever dreamed. Call the second the ‘blacker inside’ school and its essence is that stewing while waiting for evil to triumph is worse than the arrival of evil.

If Frank Miller had told this story there would have been more pages full of dramatic lighting and devoted to showing the physical pain and real dangers. Boston and Manzetti take it in a different direction sometimes merely implying the real loss and blackness, worrying about the subjective anticipation more than the excesses of some modern noir. This is not to say that the poets avoid the darkest shadows of humanity. Make no mistake: people will die in these poems and you will see it and smell it and feel it.

Noir is always about those who embrace evil, those who succumb to evil, those who attempt to sidestep it, and those lucky few that manage to survive it and find their own space. It celebrates the imperfection of what is wrong in humanity; that the darkness is awful but unable to sweep everyone into its shadow. In “Awakening” the authors write:

He visions the city in flames

and knows he must leave

before it incinerates in the

furnace of its own corruption.

The book is designed to introduce the characters and events that will lead up to “Conflagration” which can be seen as eighteen pages of transcendent crescendo in which darkness reaches its event horizon and bursts into flame consuming most of itself, but leaving enough behind for the evil to take root again.

By and large, those readers who like this sort of thing (and I’m one) have a clear idea of what this book is about by now. I consider it exceptional. I could pick a few nits. For example, one early poem and one late stanza are in a different and conflicting verb tense. I eventually just converted them in my head into the verb tense of the rest of the book. But does that really matter?

In the end, as I drive to work I’ll be thinking of Sandoval the detective, and China and Jean-Paul, and maybe visiting them again in the evening. The poem “The Great Unknown” was brilliant end to end over seven full pages. The sustained tension, interest, and fascination of this book amazes to me. Coincidentally, my collection of genre poetry books sits across the tops of two bookcases that hold my noir books. Sacrificial Nights will reside in the bookcase, not on top.

-Herb Kauderer

Originally appeared in the SFPA Reviews Page Fall 2016, and excerpted in Star*Line.

Sacrificial Nights contains poems by each of the authors separately and some in collaboration. Most of the poems are long, and they are set in Sacrificial City, a hardcore lawless urban district. The poems build, and some characters reappear from poem to poem. The poems are meant to be read in order, but I would recommend not in one sitting so that the darkness doesn’t overwhelm. There will come a point somewhere after the middle of the book where it will be hard to stop reading. Make sure you have your breath when you get there.

While I expect this book to be nominated for the Stoker and some of the poems to receive consideration for the Rhysling, it is, more than anything, noir, right down to the detective who fears his doom. There are places where fantastical things are implied, but they are generally not nailed down leaving this in the liminal spaces of speculative poetry. I am sure the whole book qualifies as horror. I leave the question of how much of the book qualifies as speculative to those who care to tease out the subtle differences.

I consider this a book of poetry noir, and nothing could be more natural. Noir is an unusual literary movement in that it came from cinema rather than the written word, and this book certainly relates back to that origin. Sacrificial Nights would make a helluva noir film full of strong images and actions. But the funny thing is, one of the hallmarks of noir film and noir fiction is its inherent poetry, the poetry of the mean streets, and a dark poetry of fatalism, betrayal, and a morality far more brutal than anything discussed in clean suburban sermons. Perhaps books such as this are its final destination.

Some of the poetry is straightforward such as this from “Requiem in a Taxi”:

The driver turns to her,

his face like that of her father,

lord of whiskey and punches,

buried now three years

in a loose blue suit.

Some is more figurative such as this excerpt from “Deep in His Coma”:

the head of the future

hissing from a manhole

with the language of a snake,

This book is really one story of dangerous streets with many characters: hookers, serial killers, arsonists, hookers, pimps, strippers, hookers, thieves, and psychopaths. There are some graphically violent moments, but the poetry doesn’t dwell on the horrific scenes. It expresses then and steps away leaving the reader to fill in as much or as little detail as she wishes.

There has been much critical discussion through the years of the difference between horror and terror with the first being a physical threat and the latter psychological. I believe there needs to be a similar division in noir between that which dwells in the physical pain and darkness, and that which dwells in the psychological darkness and fear. In the first the worst happens, and then is exceeded. In the second the anticipation of evil, corruption, and betrayal is worse, and the awful reality is almost a relief. Call the first the ‘blacker outside’ school and the key component is that the reality is worse than you ever dreamed. Call the second the ‘blacker inside’ school and its essence is that stewing while waiting for evil to triumph is worse than the arrival of evil.

If Frank Miller had told this story there would have been more pages full of dramatic lighting and devoted to showing the physical pain and real dangers. Boston and Manzetti take it in a different direction sometimes merely implying the real loss and blackness, worrying about the subjective anticipation more than the excesses of some modern noir. This is not to say that the poets avoid the darkest shadows of humanity. Make no mistake: people will die in these poems and you will see it and smell it and feel it.

Noir is always about those who embrace evil, those who succumb to evil, those who attempt to sidestep it, and those lucky few that manage to survive it and find their own space. It celebrates the imperfection of what is wrong in humanity; that the darkness is awful but unable to sweep everyone into its shadow. In “Awakening” the authors write:

He visions the city in flames

and knows he must leave

before it incinerates in the

furnace of its own corruption.

The book is designed to introduce the characters and events that will lead up to “Conflagration” which can be seen as eighteen pages of transcendent crescendo in which darkness reaches its event horizon and bursts into flame consuming most of itself, but leaving enough behind for the evil to take root again.

By and large, those readers who like this sort of thing (and I’m one) have a clear idea of what this book is about by now. I consider it exceptional. I could pick a few nits. For example, one early poem and one late stanza are in a different and conflicting verb tense. I eventually just converted them in my head into the verb tense of the rest of the book. But does that really matter?

In the end, as I drive to work I’ll be thinking of Sandoval the detective, and China and Jean-Paul, and maybe visiting them again in the evening. The poem “The Great Unknown” was brilliant end to end over seven full pages. The sustained tension, interest, and fascination of this book amazes to me. Coincidentally, my collection of genre poetry books sits across the tops of two bookcases that hold my noir books. Sacrificial Nights will reside in the bookcase, not on top.

-Herb Kauderer

Originally appeared in the SFPA Reviews Page Fall 2016, and excerpted in Star*Line.